Syndrome of Diogenes ( severe domestic squalor) symptoms,causes, and care

Syndrome of Diogenes (Severe Domestic Squalor): Symptoms, Causes, and Care

Quick Overview of Diogenes Syndrome

Diogenes syndrome is a complex behavioral disorder characterized by extreme self neglect, severe domestic squalor, and the passive accumulation of rubbish, rotting food, and waste materials. This condition primarily affects adults over the age of 60 who live alone, though cases have been documented in middle-aged individuals as well. The syndrome often remains hidden for months or years until a crisis—such as a fall, infection, or neighbor complaint—forces discovery.

It’s important to note that diogenes syndrome is not currently listed as a distinct diagnostic entity in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR) as of 2024. Instead, it overlaps significantly with hoarding disorder, depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, personality disorders, and various forms of dementia. The condition is also known by other names including senile squalor syndrome and severe domestic squalor.

The syndrome carries serious health risks: a documented 46% five-year mortality rate among affected individuals, often resulting from complications like pneumonia, malnutrition, and untreated medical conditions. Who does it affect most? Typically older adults living in isolation. What are the key features? Self neglect, domestic squalor, social withdrawal, and refusal of help. Why does early intervention matter? Because the trajectory of decline can often be slowed or reversed with appropriate support.

This article is written for families, caregivers, and medical professionals seeking a practical, clinically grounded overview of recognizing diogenes syndrome, understanding its causes, and navigating the challenging path toward care and support.

What Is Diogenes Syndrome?

Diogenes syndrome represents a behavioral and mental health pattern characterized by several interconnected features. These include extreme self neglect manifesting as poor personal hygiene and refusal of medical care, severe domestic squalor involving rotting food, accumulated rubbish, and sometimes human or animal excreta, profound social withdrawal accompanied by refusal of help from family or professionals, and passive accumulation of waste and objects without the emotional attachment typically seen in other hoarding conditions.

The term diogenes syndrome was introduced in 1975 by Clark and colleagues in the UK to describe older adults presenting with gross self neglect and breakdown of personal and environmental cleanliness. This work built upon earlier observations from the 1960s describing what was then called senile breakdown in isolated elderly individuals.

The name itself is something of a misnomer. The historical Diogenes of Sinope was a 4th-century BCE Greek philosopher who deliberately chose to live in a large ceramic jar, embracing voluntary poverty and rejecting societal conventions as a philosophical statement. Modern patients suffering from this syndrome are not making a philosophical choice—they are experiencing a pathological state characterized by involuntary decline, loss of insight, and significant health risks.

In clinical practice and medical literature, you’ll encounter various synonyms: severe domestic squalor, senile squalor syndrome, messy house syndrome, and sometimes—incorrectly—hoarding disorder. While these labels overlap considerably in everyday usage, distinguishing between them matters for accurate assessment and appropriate intervention.

Critically, diogenes syndrome differs from straightforward poverty. People with diogenes syndrome may have adequate income and resources; the severity of their squalor is disproportionate to their actual means. Community standards of cleanliness are dramatically violated not because of lack of resources but because of underlying psychological, neurological, or behavioral factors that impair self-care and environmental management.

Core Symptoms and Clinical Features

Symptoms of diogenes syndrome typically develop gradually over months or years, often remaining hidden from view until a crisis forces outside intervention. Because affected individuals usually live alone and actively avoid visitors, the condition can progress to dangerous levels before anyone recognizes the problem.

The clinical presentation clusters into several domains. Self neglect manifests as long-term absence of bathing, unchanged clothing worn for weeks or months, matted and unwashed hair, severely overgrown nails, untreated medical problems, and marked dental decay. This poor hygiene extends to complete disregard for personal appearance and health maintenance.

Domestic squalor presents as overwhelming environmental degradation: piles of rubbish throughout the living space, rotting food left to decompose, maggots and mould growth, unusable toilets and bathrooms, and powerful odours of urine, faeces, and decay. Exits may be blocked, creating significant fire hazards, and basic utilities like water and electricity may be non-functional due to neglect.

Hoarding-like behavior in diogenes syndrome involves accumulation of newspapers, packaging materials, plastic bags, broken appliances, and in severe cases, human or animal excreta stored in bags or containers. Unlike typical hoarding disorder, however, this accumulation appears passive rather than driven by strong emotional attachment to possessions.

Social and emotional signs include marked social withdrawal from family and community, suspiciousness of visitors and authorities, apparent indifference or lack of shame about living conditions, and irritability or hostility when confronted about the situation. Many individuals adamantly refuse any offered assistance.

Functional decline pervades daily activities: unpaid bills accumulate, pets or plants are neglected or die, fall risks increase dramatically due to cluttered pathways, and the individual loses capacity to manage cooking, cleaning, or basic safety tasks.

A hallmark of this condition is profoundly poor insight. Patients suffering from diogenes syndrome typically deny any problem exists, insisting they are managing “just fine” despite obvious hazards that would alarm any outside observer.

Physical complications documented in clinical study reports include dermatitis passivata—thick dirt encrustation on the skin from prolonged absence of washing—respiratory infections from mould exposure, infestations of lice, fleas, and bedbugs, and nutritional deficiencies resulting from inadequate food intake or consumption of spoiled food.

Emergency discovery commonly follows a trigger event: welfare checks initiated after neighbors report foul smells, falls resulting in injury and emergency services involvement, missed medical appointments prompting outreach, or conflicts with landlords and housing authorities concerned about property damage.

Causes, Risk Factors, and Types

The exact cause of diogenes syndrome remains unknown, but research and case reports point to a complex interplay of psychological factors, neurological changes, and social circumstances. No single explanation accounts for all cases, and medical researchers continue to investigate the underlying mechanisms.

Primary vs. Secondary Diogenes Syndrome

The syndrome divides into two categories. Primary diogenes syndrome appears without a clearly identifiable major mental illness. Approximately half the patients fall into this category, often showing entrenched personality traits such as stubbornness, suspiciousness, emotional detachment, and longstanding social aloofness. These individuals may have average or above-average intelligence and may have led successful professional lives before the syndrome developed.

Secondary diogenes syndrome arises alongside or as a consequence of identifiable mental health conditions or neurological disorders. Common associations include frontotemporal dementia, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, severe depression, stroke, and brain injury. In these cases, the squalor and self neglect appear as manifestations of the underlying condition.

Risk Factors

Several risk factors appear consistently across published cases:

Late-life stressful or traumatic events frequently precede onset. The death of a spouse or close companion, diagnosis of a life threatening illness such as cancer, forced retirement, or major financial loss can trigger the cascade toward self neglect. These traumatic events seem to overwhelm coping mechanisms in vulnerable individuals.

Long-standing social isolation or family estrangement creates conditions where decline can progress unnoticed. Without regular contact with others, there are no external checks on deteriorating self-care.

History of untreated mental disorders, drug abuse or alcohol addiction, and personality difficulties—particularly schizotypal or obsessive-compulsive personality types—increases vulnerability. These premorbid traits may predispose individuals to withdrawal and neglect when faced with stress.

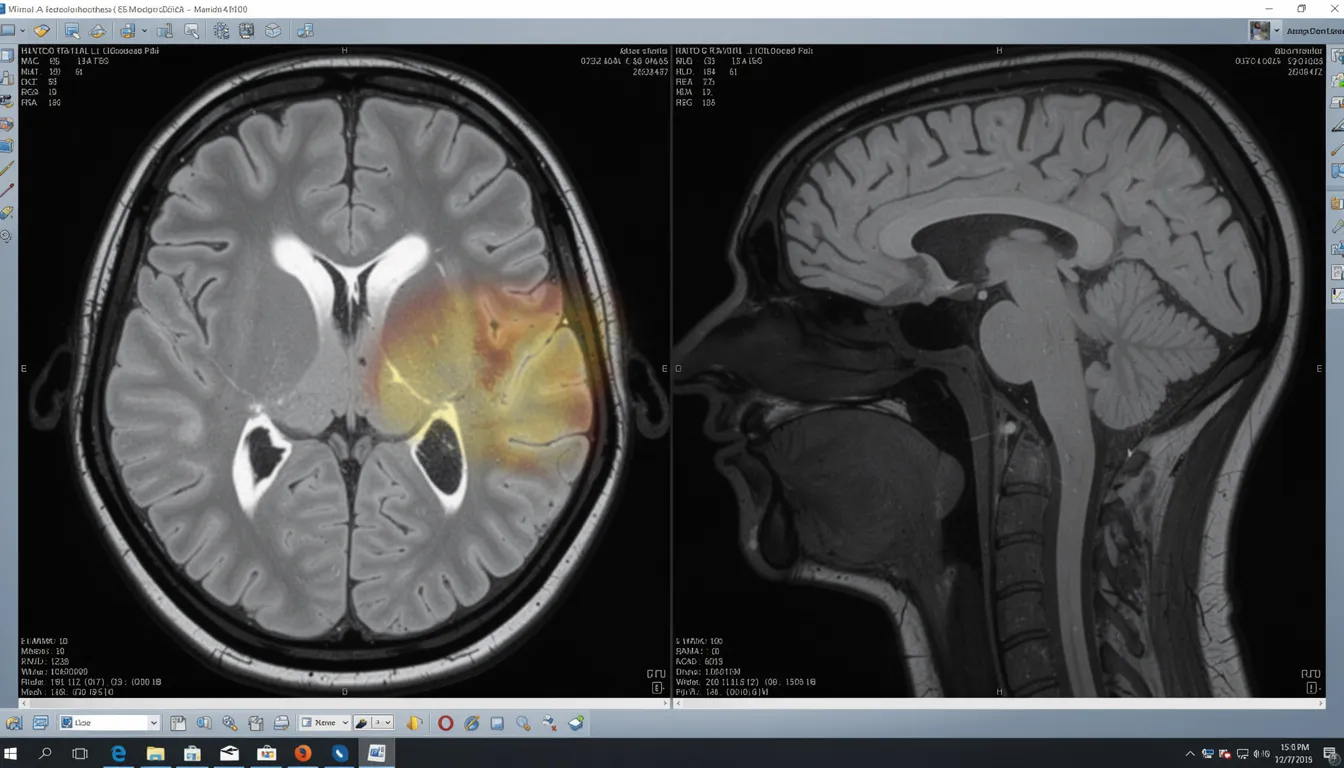

Mild executive dysfunction or frontal lobe impairment affects planning, organization, and decision-making. Neuroimaging studies have occasionally shown frontal lobe abnormalities in affected individuals, though findings are not consistent enough to establish a clear neurological cause.

Trajectory Variations

The onset pattern varies considerably. Some individuals experience sudden deterioration following a discrete event—receiving a diagnosis of metastatic cancer, suffering a stroke, or losing a spouse. Their decline is rapid and obvious.

Others follow a slow, insidious trajectory beginning in mid-life. Personality changes, gradual social withdrawal, and progressive neglect accumulate over years or decades before reaching crisis levels. This pattern often involves longstanding personality traits that intensify with aging.

Distinction from Hoarding Disorder and Related Conditions

Understanding how diogenes syndrome relates to—and differs from—other mental disorders is essential for accurate assessment and appropriate intervention. The overlaps can be confusing, but the distinctions carry practical implications for treatment planning.

Comparing Diogenes Syndrome and Hoarding Disorder

The statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5-TR, 2022 text revision) formally recognizes hoarding disorder but does not list diogenes syndrome as a separate diagnosis. This creates challenges for research, clinical coding, and treatment planning.

Emotional attachment represents a key difference. In hoarding disorder, individuals experience strong emotional connections to their possessions and significant distress when faced with discarding items. People with diogenes syndrome, by contrast, often show indifference to accumulated waste—they’re not attached to the rubbish piling around them.

The central feature differs as well. Hoarding disorder centers on persistent difficulty discarding possessions, leading to cluttered living spaces. Diogenes syndrome centers on severe self neglect and squalor, with hoarding of rubbish appearing as a passive byproduct rather than the driving behavior.

Insight and shame follow different patterns. Individuals with hoarding disorder may feel embarrassed about their living conditions but feel trapped and unable to change. Those with diogenes syndrome frequently lack shame or concern entirely, denying any problem exists.

The environmental quality differs characteristically. Hoarding disorder homes are cluttered but not necessarily filthy—pathways may be narrow, but surfaces might be relatively clean. Diogenes syndrome homes typically involve dangerous filth, rotting food, excrement, and unsanitary conditions that pose immediate health risks.

Diogenes syndrome is best understood not as a manifestation of hoarding disorder but as a special manifestation of hoarding combined with severe self-neglect—a distinct pattern requiring its own assessment approach.

Distinguishing from Other Conditions

Dementia: About 10-20% of reported cases involve dementia, particularly frontotemporal dementia. However, many individuals with diogenes syndrome show normal results on cognitive screening tests, indicating that dementia is not always present. When dementia is involved, it typically appears in the secondary type.

Psychotic disorders: Some patients with schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder presentations may live in squalor. However, diogenes syndrome can present without hallucinations, fixed delusions, or other characteristic psychotic symptoms. The absence of clear psychosis doesn’t rule out the syndrome.

Severe depression: Depression is common among people with diogenes syndrome, and clinically significant distress may be present. However, not every severely depressed person develops extreme squalor. Diogenes syndrome often includes distinctive features—longstanding personality traits, active refusal of help, and profound lack of insight—that distinguish it from depression alone.

For clinical purposes, diogenes syndrome should be considered a descriptive label that can coexist with formal DSM or ICD diagnoses rather than a mutually exclusive category. An individual might carry diagnoses of major depressive disorder, adjustment disorder, or personality disorder while also meeting descriptive criteria for diogenes syndrome.

Illustrative Case Examples

The following case vignettes are composites based on published medical literature, presented with identifying details changed in accordance with ethical standards and the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision). They illustrate common presentations and challenges.

Case One: Mid-Life Onset with Depression

A man in his early 50s was discovered by police conducting a welfare check after several weeks without contact. Neighbors had reported foul odours emanating from the property. Upon entry, officers found corridors blocked by rubbish bags stacked to chest height, a powerful smell of mould and urine pervading the space, rotting food in the kitchen dating back months, and evidence of faeces stored in plastic containers.

The bathroom was entirely unusable—the toilet and shower had not functioned for over a year. Pathways through the home required navigating around debris that posed significant fall hazards. The individual was found sitting in a small cleared space in the living room, appearing physically stable but severely unkempt.

Initial physical examination revealed thickened, overgrown toenails, skin infections consistent with prolonged poor hygiene, untreated dental decay, and evidence of malnutrition. However, there was no acute organ failure or life-threatening emergency.

Psychological assessment revealed severe depression and marked anxiety without evidence of psychosis. The patient displayed persistent social withdrawal, episodes of dissociation, and profound indifference to his living conditions. He had experienced the death of his mother—his primary social contact—three years earlier.

Outcome: Hospital admission for medical stabilization was followed by psychiatric treatment for depression. The patient initially resisted intervention but gradually accepted limited help. Home cleanup was partial; the patient discharged himself against medical advice and later relapsed into squalor.

Case Two: Late-Life Onset Following Traumatic Diagnosis

A woman in her late 70s, previously described by family as “house-proud” and socially active, began hoarding garbage and spoiled food within weeks of receiving a diagnosis of advanced heart failure. Her adult children, who had visited regularly, noticed abrupt personality changes: she refused to allow anyone inside, stopped answering phone calls, and expressed paranoid suspicions about her doctors.

A home visit by a community nurse—prompted by missed cardiology appointments—revealed domestic squalor that had developed rapidly over approximately three months. The patient showed marked indifference to hazardous conditions including rotting food and insect infestations. She refused all treatment for her cardiac condition.

Psychiatric and neurological evaluation ruled out primary hoarding disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, and frank psychosis. Cognitive screening was near-normal, though subtle executive dysfunction was noted. The clinical picture suggested possible frontal lobe involvement and severe adjustment to her terminal diagnosis—consistent with adjustment disorder with behavioral disturbance.

Outcome: The patient intermittently accepted limited help from her family but continued refusing cardiac treatment. She died at home approximately eight months after diagnosis. The case illustrates the sometimes rapid onset following stressful life events in older adults.

How Cases Come to Attention

These vignettes reflect typical pathways to discovery. Neighbors report foul odours or pest infestations spreading to adjacent properties. Mail carriers notice accumulating post and absence of activity. Housing authorities respond to complaints about property condition. Smoke from unsafe heating methods triggers fire department involvement. Missed medical appointments prompt outreach from healthcare providers. Falls or medical emergencies result in emergency services entering the home.

Assessment, Diagnosis, and Medical Workup

There is no standardized diagnostic test for diagnosing diogenes syndrome. Clinicians instead combine direct observation of the living environment with comprehensive medical, psychiatric, and social assessment. The process requires sensitivity, as patients suffering from this condition often resist evaluation.

Components of Assessment

Home visit by health or social care professionals remains essential. This documents the level of clutter, degree of hygiene breakdown, specific safety hazards (fire risk, structural damage, blocked exits), presence of vermin or infestations, and overall risk assessment. Photographs may be taken with consent for clinical documentation.

Comprehensive medical history covers current medications, substance use patterns, prior head injuries, previous mental health treatment, and functional decline trajectory. Understanding the individual’s medical history helps identify potential contributing factors. A full physical examination focuses on skin condition, nutritional status, mobility, hydration, signs of infection, and evidence of untreated medical problems. A thorough physical exam may reveal conditions requiring immediate treatment.

Laboratory workup typically includes complete blood counts, metabolic panel, liver and kidney function tests, vitamin B12 and folate levels, thyroid function tests, and other organ function tests as indicated. These identify reversible medical conditions and assess overall health status.

Cognitive screening using instruments like the ACE-III, MMSE, or MoCA helps evaluate for dementia or cognitive impairment. When screening suggests deficits—or when clinical suspicion is high—neuropsychological testing and brain imaging (CT or MRI) may be pursued to look for evidence of stroke, frontal lobe pathology, or neurodegenerative disease.

Psychiatric evaluation uses standardized tools to assess depression, anxiety, psychosis, personality traits, and hoarding symptoms. This evaluation should reference diagnostic criteria from clinical neuroscience and psychiatric frameworks while recognizing that diogenes syndrome itself lacks formal diagnostic criteria.

Collateral Information

Information from family members, neighbors, landlords, or primary care physicians proves invaluable. These sources can document the timeline of decline, describe prior personality and functioning, and provide context that the patient may be unable or unwilling to share. Understanding the psychological history and premorbid functioning helps distinguish between longstanding personality traits and acute changes.

Capacity and Autonomy

Evaluating decision-making capacity represents a critical—and challenging—component. Clinicians must weigh personal autonomy against serious risk to health, safety, or public hygiene. An individual may technically retain capacity to make decisions yet still live in conditions posing grave danger.

The tension between respecting autonomy and preventing harm creates some of the most difficult ethical situations in managing this syndrome.

Formal diagnostic labels documented in clinical records may include hoarding disorder, major depressive disorder, personality disorder, additional mental illness such as anxiety disorder, unspecified neurocognitive disorder, or psychotic disorder when appropriate. “Diogenes syndrome” or “severe domestic squalor” is then added descriptively in clinical notes to capture the full picture.

Treatment, Support, and Long-Term Outcomes

There is no single established cure or standardized treatment protocol for diogenes syndrome. Management is typically individualized, multidisciplinary, and long-term. Success depends heavily on building trust with individuals who characteristically refuse help.

Core Components of Care

Psychiatric and psychological treatment should be tailored to the individual’s specific presentation. Psychological therapies may include cognitive-behavioral approaches focusing on motivation, shame processing, trauma resolution, and executive skill building. For those with comorbid depression, anxiety, psychosis, or mood instability, medication may be appropriate when the patient will accept treatment.

Environmental interventions involve gradual, negotiated cleaning and de-cluttering. Rather than overwhelming total clear-outs, incremental approaches that give the individual some control tend to be more successful. Pest control, repairs to plumbing and electrical systems, and restoration of safe access and sanitation form part of this work. Involving the person in decision-making—however slowly—helps maintain the therapeutic relationship.

Social support and practical help may include home care services, meal delivery programs, personal hygiene assistance, help with financial management and medication oversight, and support for pets if present. A mental health provider coordinating with social services can develop a comprehensive treatment plan.

Building Trust

Many patients resist treatment, help, and even basic assessment. Building trust therefore becomes the foundation of any intervention:

Use non-judgmental, collaborative language

Allow the person as much control as safely possible over pace and priorities

Focus initially on immediate health and safety concerns rather than demanding total transformation

Accept that progress will likely be slow and setbacks common

Return consistently despite refusals—persistent gentle engagement matters

Pharmacological Options

Medication targets comorbid conditions rather than diogenes syndrome itself. SSRIs may help with depression and compulsive features. Antipsychotics may be indicated for paranoid or psychotic symptoms. Mood stabilizers may benefit those with bipolar presentations. No drug specifically targets the syndrome’s core features of self neglect elderly and squalor.

Occupational Therapy Role

Occupational therapy assessment evaluates independent living capacity and recommends assistive devices, environmental modifications, or—when necessary—transitions to supported housing or care facilities. This evaluation helps determine what level of support is needed for safe functioning.

Prognosis

Outcomes remain sobering. High morbidity and mortality characterize hospitalized cohorts, with frequent rehospitalizations and limited long-term improvement. Prognosis depends heavily on:

Availability and quality of social support

Early detection before severe medical complications develop

Severity of comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions

Whether the individual eventually accepts some degree of help

The documented 46% five-year mortality rate underscores the serious nature of this condition. Deaths commonly result from pneumonia, nutritional deficiencies, untreated infections, and complications of severe neglect.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical dilemmas pervade management decisions. Balancing respect for autonomy with duty to prevent serious harm creates genuine conflicts without easy resolutions. Some situations require consideration of guardianship, involuntary hospitalization, or involvement of public health and housing authorities when risk becomes extreme.

For some patients, inpatient treatment may be necessary to address immediate medical needs, though maintaining gains after discharge remains challenging. Comprehensive therapy approaches combining behavioral therapies, medical treatment, and social support offer the best prospects, though evidence remains limited.

How Families, Neighbours, and Caregivers Can Help

This section provides practical guidance for non-professionals concerned about someone who may have diogenes syndrome but refuses assistance. The path forward is rarely straightforward, but understanding effective approaches can make a difference.

Approaching the Person

Approach calmly and respectfully, avoiding shaming language, threats, or ultimatums. Focus on specific health and safety concerns—“I’m worried you might fall with these boxes in the hallway”—rather than criticizing cleanliness. Judgmental reactions, however understandable, typically increase resistance and damage trust.

Offer concrete, limited help rather than proposing a total transformation. Suggesting a single medical check-up, helping with one small area, or bringing prepared meals represents more achievable starting points than insisting on a complete home cleanup. Small successes can build momentum for larger changes.

Keep communication open and non-confrontational. Recognize that change is usually slow and requires repeated, gentle engagement over months or years. Single interventions rarely succeed; sustained relationship matters.

When and How to Involve Professionals

Contact primary care physicians if there are concerns about untreated medical conditions. Community mental health services can provide psychiatric assessment and ongoing support. Adult protective services (or equivalent agencies) respond to reports of self neglect elderly individuals living in dangerous conditions.

Housing authorities or environmental health officers should be contacted if the property poses fire risk, structural hazards, or public health threats such as infestations spreading to neighboring dwellings. These authorities can mandate certain interventions when risk is severe.

Call emergency services or law enforcement when there is immediate danger: serious medical emergency, imminent fire risk, or an adult who appears incapable of caring for themselves. Crisis intervention may be necessary even against the individual’s wishes.

Documentation and Self-Care

Caregivers and concerned family members should document patterns over time. Record missed appointments, reports from neighbors about worsening odours, evidence of infestations, falls or injuries, and any changes in condition. This documentation helps professionals understand severity and duration when formal involvement becomes necessary.

Support groups for caregivers dealing with hoarding and self-neglect situations exist and can provide emotional support and practical strategies. Family members experiencing the emotional toll of dealing with severe domestic squalor and repeated refusals of help deserve support themselves. This situation is genuinely difficult, and caregiver burnout is common.

Research Gaps, Ethical Issues, and Future Directions

Despite case reports and small studies dating back to the 1960s, diogenes syndrome remains under-researched. The American Psychiatric Publishing has not included it as a formal category in diagnostic manuals, and no universally agreed diagnostic criteria exist.

Key Research Gaps

Standardized definitions distinguishing diogenes syndrome from hoarding disorder, severe self neglect, and dementia-related squalor remain elusive. The field lacks clear consensus on where these categories begin and end.

Large, controlled studies on prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes across different countries and healthcare systems are virtually absent. Most knowledge derives from case reports and small case series, limiting generalizability.

Evidence on which combinations of psychological therapies, medications, and social interventions are most effective remains limited. Treatment recommendations rest largely on clinical experience and extrapolation from related conditions rather than robust clinical study findings.

Ethical Challenges

Managing capacity and consent when individuals refuse help yet live in life-threatening conditions creates profound ethical tension. Respecting autonomy is a fundamental principle, yet allowing someone to die of malnutrition or infection in preventable circumstances violates duties of care.

Balancing individual rights, property rights, and public health needs—such as when infestations spread to neighboring dwellings—requires navigation between competing legitimate concerns. There are no simple answers.

Ensuring that interventions respect dignity and autonomy means avoiding purely punitive or forced clear-outs that can traumatize patients and permanently damage therapeutic relationships. Even when intervention is legally mandated, how it is conducted matters enormously for future engagement.

Future Directions

Debate continues over whether diogenes syndrome should be formally recognized as a distinct diagnostic entity in the DSM and ICD frameworks. Such recognition could improve research funding, clinical coding, and treatment planning. Critics argue that it overlaps too much with existing categories to warrant separate status.

Neuroimaging research may eventually identify biomarkers—perhaps frontal lobe signatures—that help identify vulnerable individuals earlier. Longitudinal studies tracking isolated elderly populations could identify early warning signs before full syndrome development.

Public health campaigns targeting isolated seniors, combined with proactive community screening, could potentially lower the grim mortality statistics through earlier detection and intervention. Training for primary care providers, home health workers, and social services staff on unmasking diogenes syndrome in its early stages represents a practical near-term goal.

Closing Thoughts

Although challenging, compassionate, coordinated care can improve safety, health, and quality of life for people living in severe domestic squalor. The condition is serious—but not hopeless. Early detection, patient relationship-building, multidisciplinary collaboration, and sustained support offer the best prospects for positive outcomes.

If you’re concerned about a family member, neighbor, or patient who may be experiencing this syndrome, don’t wait for a crisis. Reach out to healthcare providers, social services, or mental health professionals. Small steps matter, and the person you’re worried about deserves the chance for a safer, healthier life.

Latest news

Delve into the essential stages of trauma scene cleanup in Atlanta, GA, providing insights into professional practices that ensure thorough restoration.

Read More

Learn why professional biohazard cleanup in Atlanta is crucial for safety. Discover the risks of DIY cleanup and the benefits of hiring certified experts.

Read More